Professor Connell Fanning and Dr Assumpta O’Kane

The disparities in earnings between men and women are being reported in accordance with the Gender Pay Gap Information Act, Ireland, 2021. In studies of the pay gap being announced, there will be many reasons given for the differences, but a seemingly small but crucial one is likely to be left lurking in the background.

That is the requirement for ‘leadership’ which is frequently but thoughtlessly inserted into many high-level job descriptions for appointments and promotion. This opens the way at the outset to discrimination against women since what is meant by ‘leadership’ is rarely spelt out and so is open to abuse. From then on gender is probably unavoidable especially when ‘leadership’ is allowed to be understood in terms of personal characteristics, attributes, and behaviours, as is most often the case.

This approach has long-term consequences. For example, the problem of imbalance on board of directors in Ireland was reported as follows in 2017 in The Irish Times: “When it comes to women directors on listed company boards, the needle is stuck on the dial.” In other words, implicit or unconscious prejudice and bias often shapes decisions when responsibility for selecting directors, and indeed other senior managerial positions, especially for CEOships and managing directors, is exercised. Undoubtedly, there were also implications for selecting the succession pipeline.

The problem with personal characteristics approaches to ‘leadership’ is that they inevitably open the door to implicit prejudices and biases, and it also serves to make them seem almost natural and correct.

Unconscious bias about leadership is everywhere

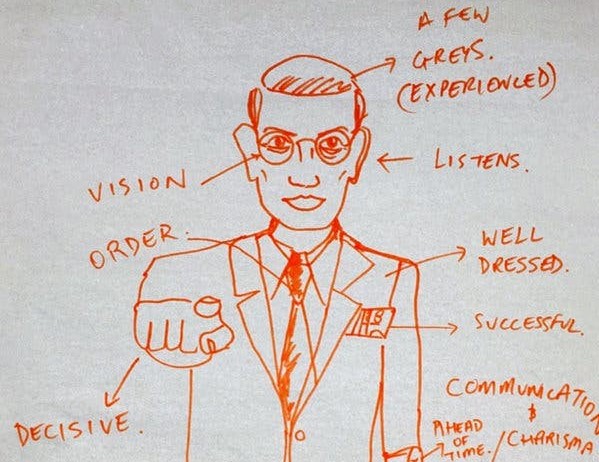

That such automatic discriminatory turns occur is vividly illustrated by Heather Murphy in a New York Times article (16 March 2018), ‘Picture of a Leader, Is She a Woman?’, reporting results of an exercise in which a series of sketches were drawn by various people on foot of a simple neutral prompt: “Draw an effective leader.”

Asking people to draw their image of a ‘leader’ resulted invariably in images of ‘leaders-as-men’. The article explained how this exercise arose accidentally when Professor Tina Kiefer of Warwick University was conducting a workshop of executives who did not speak much English.

Professor Kiefer found the results were almost always the same: both men and women almost always draw men, and she is quoted as saying, “Even when the drawings are gender neutral, the majority of groups present the drawing using language that indicates male (he) rather than neutral or female”, although her clients often insisted that what they meant by ‘he’ is actually both’.

The article refers to other studies on the line of investigation opened up by this exercise. One found that getting noticed as a ‘leader’ in the workplace is more difficult for women than for men even when a man and woman were reading the same script. In another, about a sales team in a fictional insurance company, the person labelled ‘Eric’ was more often identified as ‘leader’ than the person labelled ‘Erica’ in an exercise in which participants were asked to rate the speaker on the degree to which he or she had “exhibited leadership”, “influenced the team”, or “assumed a leadership role”.

The explanation proposed by the researchers is that “People have these prototypes in their head about what a leader looks like. When they see an individual, we ask, ‘Do they fit that?’” and that when we “process information through the lens of stereotype” our interpretation may be “consistent with stereotyped expectations rather than objective reality” in a self-reinforcing cycle of “confirmation bias”.

These are two of the examples reported and referenced in the article. In the particular instances reported above we see in practice that people genderise leadership, even if unintentionally. There is a constant stream of studies, reports, and personal experiences recounting how women have been side-lined in meetings, boards of directors, and elsewhere in business organisations.

Bias about leadership is long standing

Gendering of ‘leadership’ has been deeply ingrained in our everyday, unconscious thinking, especially male thinking, despite all the advances of recent decades.

Mary Beard, in Women and Power: A Manifesto, sketches historically how women who ‘dared’ speak out in public spaces were treated and how, as a general matter, they were silenced.

Beard makes the point by noting how women are not included in, what she calls, the ‘images’ of leaders that we hold in common and individually with her example about professors in universities. While noting that there are now more women in what would be considered ‘powerful’ positions than was the case even ten years before her writing, she, nevertheless, holds to her basic premise that “our mental, cultural template for a powerful person remains resolutely male. If we close our eyes and try to conjure up the image of a president or – to move into the knowledge economy – a professor, what most of us see is not a woman.”

Then she makes an eye-opening admission that this is: “ just as true even if you are a woman professor: the cultural stereotype is so strong that, at the level of those close-your-eyes fantasies, it is still hard for me to imagine me, or someone like me, in my role.”

Beard did a simple check about her personal view: “I put the phrase ‘cartoon professor’ into Google UK Images: ‘cartoon professor’ to make sure that I was targeting the imaginary ones, the cultural template, not the real ones; and ‘UK’ to exclude the slightly different definitions of ‘professor’ in the USA. Out of the first hundred that came up, only one, Professor Holly from Pokémon Farm, was female”. She continues: “[t]o put this the other way round, we have no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man”.

Beard, turning specifically to ‘leadership’, says that she would like “to try to pull apart the very idea of ‘leadership’ (usually male) that is now assumed to be the key to successful institutions, from schools and universities to businesses and government.”

Reinventing leadership: a better way of thinking

This is what we effectively did in our recent book, The Leadership Mind, in which we demonstrate that properly analysed and conceptualised ‘leadership’ as such is a gender-free concept from the outset.

Thus, we do not need to start with a gendered concept and then have the struggle of overcoming the in-built bias to get to an unsatisfactory ‘gender neutral’ position, with all the obstacles involved (unless of course the struggle itself is the point which, as with some movements, it can be).

Instead, we can start from a clear ungendered conceptual position. This will then require those advancing the claim that ‘leadership’ is a male prerogative in some (biological?) way to justify that claim. Then, if they are unable to do so validly, their ‘reasoning’ would be exposed for what it must be: a personal or cultural bias, prejudice, or ignorance.

We argue that this gender is a corruption of the concept of ‘leadership’.

And we ask, how is this problem to be overcome?

Leadership, by definition, should not lend itself to such corruption.

So what do we do?

We can start at the beginning by changing the conceptual game by addressing How We Think? We come back to the basic question ‘what is ‘leadership’?’. What do you think ‘leadership’ is? And, when you think about it, have you genderised it without good grounds for doing so? Can you justify and validate those grounds? If not, will you liberate your mind and use an ungendered concept of ‘leadership’, such as offered in The Leadership Mind (2022). If you are in a position of responsibility for developing people, will you think anew when talking about leadership development?

Professor Connell Fanning is Founding Director of The Keynes Centre at University College Cork, and Dr Assumpta O’Kane is a Chartered Occupational Psychologist. The Leadership Mind (The Keynes Centre, UCC, 2002) is available in Waterstones Cork, Hodges Figgis Dublin, UCC Lowercase Bookshop, and can be ordered on Amazon, UCC Online Shop, and at good bookshops (ISBN: 978-1-7391152-0-3).