Connell Fanning

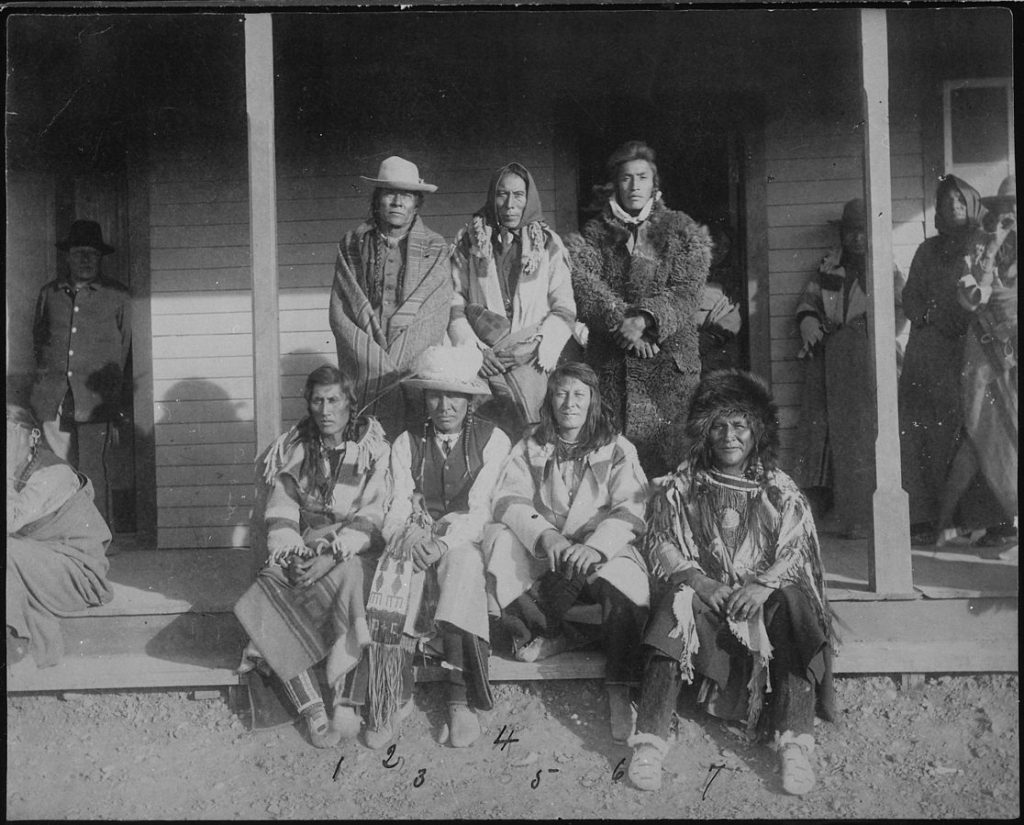

Plenty Coups was the last, greatest chief of the Crow Nation[1], a once vibrant native tribe of nomadic warrior hunters living around what today is called the Yellowstone River Valley on the North American continent. He was interviewed shortly before he died about his world and that of his people.[2] The chronicler of his life records him as saying:

“…when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere.” [3]

How could nothing happen after the buffalo were gone? How could his people not ‘lift their hearts up from the ground’ again? How could there be ‘little singing anywhere’?

When the Crow Nation lost their struggle with the invading United States in the middle of the 19th century they were forced to move on to so-called ‘reservations’. In that move, these Native American people lost more than their expropriated native living space, their physical resources, from this catastrophe. They were also coerced into giving up their tradition of thought, based on their nomadic, warrior, buffalo-hunting centered way of living, and made to ‘settle down’ to a radically different life on the limited and impoverished land allocated by the invading U.S. Government. Thus, they were made to suffer the loss of their conceptual resources through which they had made sense and understood their immemorial world.

The Crow people lost their way of knowing their past, present, and future; their way of making sense of the world in which they lived and had expected to continue living; their way of organizing their experiences into their meanings and truths; and their mode of constructing their reality which governed their conduct. They lost their entire ‘meaning and truth making system’ as they were abruptly ejected from their conceptual world.

This loss of concepts, an intellectual trauma well expressed in Plenty Coups statement above, was every bit as real as the physical loss of their lands and livelihood. It was not just a matter that their ‘traditional way of life had come to an end’ from then on. Looked at from the standpoint of the individual person, it was that:

“I no longer have the concepts with which to understand myself or the world … I have no idea what is going on.” [4]

The cultural devastation accompanying the destruction of their way of living encompassed their how to think, the fundamentals of the way of life they inhabited, a way of life expressed in a culture now obliterated by another culture.

The experience of Plenty Coups – ‘after this nothing happened’ – is universal and conveys the vulnerability of us all as human beings when civilizations collapse. What we see in the world depends on how we think about it and using concepts is one of the primary ways we think about it. Concepts are ‘lenses’ through which we ‘see’ the world. They are, therefore, one way we relate to the world in which we live, to others, and to ourselves.

Plenty Coups had suffered a catastrophic loss of concepts, of the ‘lenses’ through which he saw ‘events’ becoming events as he was seeing them through those lenses.[5] He could no longer ‘see’ anything, that is, any truths and meanings of significance, once these ‘lenses’ were taken from him: ‘after that, nothing happened’, although, of course, he continued to live on the reservation, travelling to Washington, D.C., and so on, so things were happening all around him seen from our different standpoint. They just no longer had significance because he had lost his conceptual apparatus for constructing his meanings and truths since his ‘world’ was now overwhelmed.

The case of Plenty Coups is an example of the effect of the loss of concepts by a person on their life. We are all vulnerable to such loss even if we are largely unaware of it as we live our daily lives.[6] In this regard, we may note Keynes’s observation when he was reflecting on his earlier beliefs:

”We were not aware that civilization was a thin and precarious crust erected by the personality and the will of a very few and maintained by rules and conventions skillfully put across and guilefully preserved.”

The loss of concepts, however, is not just a matter of the fundamental uncertainty of the human condition at the grand scale of civilizations. At the individual or group level we are vulnerable to trauma shaking the foundations of the ‘meaning making system’ that we are at any moment. The experience of Plenty Coups illustrates the power of concepts in our lives and points to the subconscious sense of vulnerability to loss of concepts, that our outlook itself might collapse, and that can provoke reactions, for example, of intolerance in us.[7]

This is a fact of life as human beings on this earth we rarely recognise, allow for, and allude to as we go about our usual activities. We do not usually stop and think about it, reflect on the implications for living at this uncertainty. Yet we may experience such trauma as loss of concepts when, for example, the organisation for which we have worked for decades, to which we have dedicated our careers and in which we have invested our labour and commitment, may be merged or taken over by another organisation. The conceptual resources we have built up over time through our experiences may be rendered redundant in an instant although we may not approach it in those terms.

A little reflection on concrete examples throughout our lives will show that most of us experience such loss of concepts throughout our lives although, perhaps not to the degree of Plenty Coups and his people, and, like him, we may not have looked at the experience in that way since we do not often pay attention, we do not tend to stop and think about our conceptual resources.[8] We take them for granted on the large and small scale of our lives.

[1] Apsáalooke or Absaroka, ‘children of the large-beaked bird’

[2] This section draws entirely on the material and argument of Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2006. This is an extraordinary book about the vulnerability that characterises the human species as a whole and the possibilities for cultural catastrophe we all must live with on this earth and which we are getting a sense may be coming to us. We tend to dislike the overused descriptors ‘necessary’ and ‘essential’ in book reviews, yet this is a book to which we suggest these terms validly apply. It is a timely read for our times to open our minds as we face the nexus of climate disaster, political crises, and public health emergencies.

[3] Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation:2 (emphasis added), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2006.

[4] Lear, 2006:48 (emphases added).

[5] We may be facing a similar collapse of our conceptual resources as the unfolding climate crisis takes hold of the earth and we are finding that our ingrained ways of thinking are inadequate to grasping the magnitude and implications of this environmental destruction.

[6] John Maynard Keynes, My Early Beliefs, in John Maynard Keynes, The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume X, Essays in Biography: 447, Macmillan – Cambridge University Press, London, 1972.

[7] Lear, 2006:7.

[8] Lear, 2006:10.